|

|

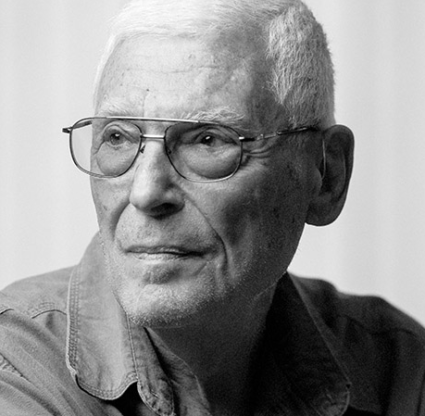

Nathan Hill's mother, photographed by Shawn Poynter. |

For most of my adult life, I’ve observed Mother’s Day very quietly, with a simple phone call. “Happy Mother’s Day,” I tell my mom when she answers, and she thanks me for calling and then my dad jumps on the line and we have a normal conversation, giving updates, talking about the news. It’s not that we don’t celebrate Mother’s Day—it’s just that our celebration is restrained. We’re a Midwestern family; we generally prefer understatement to big dramatic gestures. If I were to do something extravagant—like send a big flower bouquet, or an elaborate gift basket, something like that—my mom would probably wave her hand and roll her eyes and say, “You shouldn’t have gone to all that fuss.”

But as Mother’s Day 2017 approaches, I’m aware that this year is a little different. Because this year I published a novel that a lot of people read, and it’s a novel about a bad mother.

A very bad mother, indeed: The character in my book is cold, distant, haughty, secretive, and, worst of all, she abandons her family when her son is 11 years old. I warned my mother about this, perhaps six months before the book was published. I tried to explain to her how a novelist works: We invent characters, but surround those fake people with real details. I told her that the mother in my novel is not her, exactly, but that the two of them do share certain mannerisms, certain idiosyncrasies, certain biographical details (primarily, they both grew up in the same small Iowa river town). I explained to my mom that even though this character is not based on her, she would nevertheless find her quite familiar, and that’s because while I was writing her, whenever I’d need a poignant mom-type detail, I’d pull first from my real life. As a result, a lot of my real mother sort of oozed into this invented version.

“Oh, Nathan,” my mother said when I told her this. “You know what people are going to think?”

Which is also a trait of Midwestern families: We care deeply about what people think.

But my mother was right to worry. People did indeed make certain assumptions. Imagine having to explain to a reporter from The New York Times that, no, in fact, my mother did not abandon me when I was a child. Imagine having to explain to the many readers who assumed my mother is unforgivably horrible that, actually, she’s just the opposite: warm and supportive and generous and kind, a person who never abandoned anything, ever.

So this year’s Mother’s Day feels extra-special important because my mom has been unfairly maligned, and it’s all my fault. This year’s Mother’s Day feels like it requires a larger gesture than a simple phone call.

|

|

The author, photographed by Erik Kellar |

It puts me in mind of the last time I tried to make Mother’s Day really significant and unique. This was many years ago. I think we were living in the suburbs of Chicago at the time, which would have put me in the third grade or fourth, which would have made this the mid-’80s. My family moved around a lot when I was a kid, and so my memories are all organized this way: geographically. Childhood is less a river that flows into the present and more a series of islands: a place, then another place, then another place, and so on. And in this memory, the particular place is mom and dad’s bathroom, filled with all the exquisite ornaments of the adult world: razors and perfumes and various mysterious salves and ointments. I’ve snuck in here because I want to do something special, because Mother’s Day is coming up, and unlike the usual child’s response to a parent’s life event—which is to blithely and barely note it because it has not occurred to you that your parent has any interest or excitement or life outside of you—this year is different. This year I am feeling expansive and generous. This year I will give my mom a gift, my own gift, from me to her, and the gift will express everything I want to express to her.

But as soon as I decide on this plan, a basic problem presents itself: I can’t buy anything for her. It’s not like I can head off to the mall with a credit card. I’m 8. And anyway my allowance at this time is maybe a buck a week, so even if I somehow got to the mall without my mom knowing, I could afford, at most, a gumball. So the gift, I decided, needed to be handmade. Of course it did. And I told myself this was, in fact, better: There was no doodad from the mall that could say what I needed to say. My handmade gift would be more real, more authentic, than anything I could purchase at a store.

A card. A beautiful, handmade, handwritten card that maybe had a quaint little message on the inside, a bit of straight-from-the-heart poetry that would, hopefully, if I did it correctly, make my mom happy, or maybe even make her cry.

So I pilfered some construction paper from the school’s art-room stores, and using those fat awkward public-school safety-scissors that have long ago gone so frustratingly dull that they don’t so much cut the paper as brutally pinch it beyond the paper’s tolerances, I fashioned the rectangular card, I cut the jagged letters for the front, where I tried to come up with something witty but ended up with “Happy Mother’s Day” because, I decided, you might as well stick with the classics. Then I glued everything down with glue sticks that left behind little boogers of dried yellow paste, put it in my backpack where it got crinkled on the bus ride home, and took it out in my room in order to write my heartfelt message on the inside. And I thought and thought about it, and what I ultimately came up with was:

I made this for you!!!

Which struck me immediately as all wrong—selfish and prosaic and not nearly good enough to stand up to the occasion.

So this is why I’m in mom and dad’s bathroom. I’m looking for something else, something I can do to the card to give it that added dimension, that little extra oomph, that special something that can communicate what my banal words cannot. And I believe I’ve found it when I locate, on the countertop, the slim oval container of my mom’s deodorant.

I don’t, at this time, know what deodorant is, or what it’s for, or why people wear it, or why the people on TV in deodorant commercials always seem so happy and jazzed up about it. Mostly I know that it smells good. And this is my brilliant plan: I will give mom a Mother’s Day card that may not look good, but it will smell good.

|

|

The author with his mother. |

This strikes me as unbelievably creative. I’d never even heard of a Mother’s Day card that smelled good. Take that, Hallmark.

So I pop the cap off the deodorant and rub it all over the Mother’s Day card and then give it to my mom, expecting praise.

Yes, that’s right, here was the woman who birthed me, who raised me, who applied Band-Aids to my wounds and taught me how to read, who nourished me and tucked me into bed each night, who provided a warm and safe place for me to live and taught me countless lessons about understanding right from wrong. And to show her my gratitude, I gave her a card smeared with her own deodorant.

My mom entertained me when I was a child, played games with me that must have been so tedious in their repetition. I remember one in particular where I was a police officer and she was an innocent witness and I ran to her and said, “Where did the bad guy go?” and she’d say, “I’m not telling!” and then I’d flash my plastic policeman’s badge just to show her who’s boss, after which she said, “Oh, he went that way,” and for some reason this game was intoxicating for me. I made her do it over and over, which of course she did, never once betraying how boring and monotonous this must have been, because I was having fun, and that, for her, was more important.

And in return, I gave her a crinkled construction paper card that smelled like her own armpit.

My mom cried when she dropped me off for college, and again two years later, when she helped me move into my first slummy apartment. Her advice about life was always simple, direct and true. When I told her, at age 9, that I wanted to be a professional baseball player, she said, “Well, you’re gonna have to work really hard.” When I told her, at age 10, that I wanted to be an astronaut, she said, “Well, you’re gonna have to work really hard.” When I told her, in high school, that I wanted to be a novelist, she said, “Please don’t.”

And then she said, “But if you do, you’re gonna have to work really hard.”

She volunteered in my kindergarten class and helped me at home with my reading skills, showing me flashcards with individual words or punctuation marks printed on them, then arranging the cards to build sentences, then whole paragraphs. She worked with me on a speech issue that made me pronounce the word “cinnamon” like “thinnamon.” She helped me write my first book, in the third grade, a Choose Your Own Adventure story called The Castle of No Return, where you are a brave knight and you go save a beautiful princess. In one of the story’s branches you are murdered by a robot (why a robot would appear in a medieval castle, I have no idea), and mom wanted to soften the ending a little, suggesting we replace You are murdered with You are gone, which seemed to her less deranged and homicidal. She read me books and then gave me books to read on my own. I remember reading Moby Dick one night and mom came in to tuck me into bed and I put up my index finger in the be-with-you-in-just-one-second gesture because I hated stopping in the middle of a sentence and she just patiently waited for me as I made my way through one of Melville’s many-lined whoppers. In fact, many of the things I associate with writing and reading I trace back to stuff mom gave me or taught me.

And I, in turn, gave her a torn-up paper card covered in Arid Extra Dry.

My gifts never seemed to measure up to what I intended from them. One Christmas when I was a teenager and mom and I had been bickering the way parents and teens are wont to do, I gave her a bathtub whirlpool massaging jet system thing—the idea was that if I was being a jerk again at least she’d be able to relax in the tub afterward—but the contraption was so loud and obnoxious it was like trying to relax while lying directly next to a lawnmower.

No, all my gifts to mom have fallen short—and maybe that’s because I’m not a very good gift giver, but it’s also because of this: There’s just no gift that can measure up to her love. Which is why her love is so powerful—it’s freely given, and overwhelming.

So maybe the best thing I can do this Mother’s Day, the best gift I can give in this, the year I’ve made thousands of people question her parenting, is simply to say thank you, and do so very publicly. Thank you, mom, for the books and the lasagnas and the German chocolate birthday cakes and breakfasts in bed and taking care of me through fevers and colds and vomit and jaundice and colic and a tonsillectomy and a spinal tap, and thank you for staying home with me when I was sick and for applying medicines to unspeakable places, and thank you for teaching me how to read and write and taking me to piano lessons and Cub Scouts and Little League and band practice, and thank you for always sending birthday cards that arrive exactly on my birthday every time even though I have never been able to do this in my life, and thank you for the hearts carved into peanut butter sandwiches, and the advice about crushes and heartbreaks, and thank you for a thousand other small moments when you gave comfort when comfort wasn’t otherwise available.

And thank you, especially, for what you did on that one Mother’s Day many years ago, when I gave you a ragged handmade construction-paper card streaked with dried glue and deodorant, and you somehow stifled what must have been a very compelling urge to laugh, because you knew that laughing would make me feel awful, and so instead you made a big show about how amazing and creative my gift was, and you put it up there on the fridge, and I felt amazing. Even my gift to you ended up being, in the end, your gift to me. Such is the selflessness of a mother’s love.

So thanks, mom, for all of it. And I’m sorry I’ve once again failed to buy you something for Mother’s Day. Instead, I’ve gone the handmade route, writing this little essay. I hope you like it. I made it for you.

Nathan Hill’s best-selling novel The Nix was named the No. 1 book of the year by Audible and Entertainment Weekly, as well as one of the year’s best books by The New York Times, The Washington Post, Amazon, Newsday, Library Journal and many others. The Nix was a finalist for the Leonard Award from the National Book Critics Circle for Best Debut of 2016. It will be published worldwide in more than 25 languages. Nathan Hill lives in Naples.