It is 2 a.m. I am sitting beside my mother’s bed in ICU listening to the rhythm of her breathing. She wears three plastic bracelets on her arm—a thin white one with her name, Leah Monk. A red one with Fall Risk printed in thick black letters. And the blue one, the one I hate, but chose anyway, the one that says Do Not Resuscitate. Earlier today the nurse showed me my mother’s chest X-ray. I wish she hadn’t. It will haunt me now, her lungs filled to the brim with pneumonia, how it looks like some horrific white mold that gets in the wall of your house forcing you to vacate. Her breathing is magnified by the BiPap machine, rising and falling as if piped from surround sound speakers, a kind of symphony. It enters the pores of my skin and darts along my ribs. It is like a bellows in my head. I find myself synchronizing my breath to it, but it’s too fast and I fall out of sync. I want to preserve the sound somehow. This is my mother breathing.

Then suddenly, a flash of memory …

I am catching fireflies in the front yard. We called them lightning bugs, as one is supposed to in Georgia. How old was I? Seven? No, 8. Definitely 8.

That was the terrible summer I didn’t want to be away from my mother. I have always thought of it as the strange summer, my weird phase, a tiny black hole in my childhood full of mystery and ache and something I could never quite identify, perhaps something beautiful, I’m not sure. Later on no one would speak of it. Yet it has always stayed with me, wanting to be talked about. How funny, how telling, that it should surface now. That summer, for reasons no one could fathom, I suddenly became terrified for my mother to be out of my sight. I would be outside under the carport with my dolls and it would strike me that she wasn’t there. I would be overtaken with the need to find her, to make certain she was present and accounted for. Everything depended on it—the world depended on it. I would lay down the dolls—there were so many of them, the black-haired Barbie, the redheaded Madam Alexander, the bald-headed baby named Sally—and I would bolt into the house toward the kitchen a little frantic, calling for her, and there she would be, my mother, the source of everything. She was the world in its orbit. She was the moon shining over me. And I was Dorothy of Oz arriving home again, back in the place of belonging.

Ah, the place of belonging—that elusive locale in the landscape of the soul. A place no GPS can find, a place even Google cannot map. I’m sure, though, it lies in the Back Country of the heart, somewhere behind the left ventricle. It’s the place where, despite whatever despairs and ecstasies have befallen us, we are home and all is well and all is well.

Finding my mother in the kitchen, I would wrap my arms around her waist and draw from her whatever missing thing I needed. Then I would return to my dolls and all those doll clothes my mother had sewn. Little ice skating suits, cheerleading outfits, lounging pajamas.

When that summer turned to autumn and school began, I balked. I didn’t want to go to third grade. For how would I find her? Where would she be? What if she wasn’t there? I went to school, of course, but not easily. In an effort to ameliorate my fears, which must have been badly showing, my teacher, Mrs. Houston, moved my desk beside hers. I’m talking about up to the front of the room facing the rest of the class. I didn’t even mind all of those small perplexed faces staring at me. Mrs. Houston’s pale blue cardigan sweater hung on the back of her desk chair and when the urge came over me to go running for my mother, I would hold onto the sleeve like some sort of tether. Often my mother would appear during recess. How did she know I needed a glimpse of her? Had the teacher called her? I have no idea, but there she would be, sitting in the car parked on the street beside the playground. I can still see her perched behind the steering wheel in the 1956 black Chevrolet. Me, playing tetherball, one eye on the ball, one eye on my mother. She never got out of the car. She only sat there where I could see her, the sturdy presence, the moon shining. I would return to the classroom dragging my feet, looking over my shoulder, the last child out there. Waving. My mother waving back. Oh, but the world, it had been righted again.

What was going on with me during that awful time that began in July and stretched to October, that 3-month descent into little girl hell? Was I suddenly conscious of my mother’s mortality? Was I afraid she would die? Did I worry she would abandon me? Or was this some archetypical childhood fear playing out, albeit in dramatic fashion?

It occurs to me for the first time that the residue of this strange childhood episode had spilled over into my first novel, The Secret Life of Bees. I’d written about a girl, Lily, whose mother abandoned her for a time, then died young. What does Lily do? She bolts from her life and goes in search of her mother, of a mother, of some moon to shine over her.

Who can explain why a novelist writes what she writes or why a child fears what she fears? I only know the journey to find the place of belonging, not just in the world out there, but in the spaces of one’s own heart, became a concern of my creative life.

In the years since The Secret Life of Bees came out, I told audiences probably a thousand times that my mother was not like Lily’s mother. There are all kinds of parents, just as there are all kinds of people. Some leave their children, some abuse them, and some, for whatever reasons, fail to love and nurture them, but through the vagaries of fate, I had the best of mothers, the kind who made doll clothes and hammered nail holes into the top of jar lids so lightning bugs could breathe, the kind who was always-always there, which makes the summer I was 8 all the more bizarre. It finally went away—the sudden seizure of fear, the scrambling after her, racing onto the playground looking for the black Chevrolet. It stopped abruptly like a fever breaking, and we never spoke of it.

The memory of lightning bugs in the front yard had brought it back. Why was that? I remember darting through the pines chasing the luminous flecks, collecting the poor creatures in a Mason jar, mesmerized at the way they made their own light. They were the light of their own world. Imagine. How did they do that? There must’ve been a dozen of them in my jar when I brought them inside that night. I took a bath with bubbles and put on shorty pajamas. They were blue with white print flowers. My mother had made them herself on the grand Singer sewing machine, which she loved more than she would ever love a smartphone. Then amid the smells of soap and clean skin and wet hair, my mother took the jar of bugs and placed it on my bedside table and turned off the lights. We watched their razzle dazzle for long minutes, not speaking, barely moving. I remember now her breath filling the darkness. How I leaned into it. I am here, I am here. The symphony. The melodic sound of the Back Country.

It is the same breath I hear now 60 years later as I sit in the green chair in the middle of the night in the darkened ICU room in Georgia. I gaze at her as she lies in the pulmonary bed, folded in the deep shadows of the room, the elaborate oxygen delivery system strapped over her head like some voluptuous Hazmat gear, her white hair glowing on the bed sheet. There are no lightning bugs. No living breathing night light. Only green dots on the heart monitor moving with tiny trailing wings across the screen. There are fiery red lights on the intravenous contraption and shiny gold ones on the oxygen machine. A roomful of winking, blinking lights, the razzle dazzle, and I have that urge again for the first time since I was 8 to tear from the carport, from the green chair, and run blindly to find her. But which mother? The young one who sat beside me on the bed as we watched the lights in the Mason jar? The 95-year-old with the pneumonia-ravaged body whose light seems so dim I want to cup my hands around it? Or the mother in myself who lives in the Back Country behind my left ventricle?

The urge hammers in me, but I sit unmoving and listen to the whirlwind of breathing in the room, how it blows through the rafters in my chest. For a moment I consider taking out my iPhone and recording it, then tell myself no, it would never come out as precise as I hear it now.

I glance at the round clock on the wall. 4:34 a.m. Is there anything to do but sit here in this swarm of technological fireflies and cherish these breaths? I do not want them to leave her, but when they do, the sound will go on in me as it always has, the steady metronome of her presence.

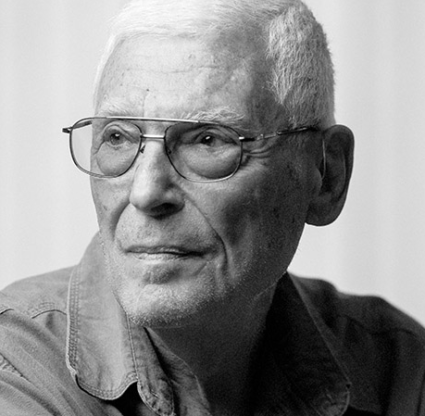

Sue Monk Kidd is the best-selling author of The Secret Life of Bees, The Mermaid Chair, Traveling with Pomegranates: A Mother-Daughter Story, The Invention of Wings and other acclaimed works. She was honored as one of Gulfshore Life’s 2017 Men & Women of the Year.