At age 49, I became a student at Florida Gulf Coast University, where I teach journalism. I applied for admission, sent in my transcripts, updated my immunizations, received an acceptance and enrolled in Beginning French I.

On the morning of Aug. 17, 2016, I entered Madame Tatiana Schuss’ classroom and took a seat in the front row at a desk too small for my laptop, coffee tumbler, legal pad, highlighters, pens and textbook. I was learning French because of a book idea that wouldn’t let go of me—about women who were labeled hysterical and institutionalized in 19th century Paris. Doctors hypnotized them in public “lessons” that served as entertainment for many.

To write the book, I needed to read source material in French and send simple emails to librarians, archivists and scholars.

I look back on that self at the classroom desk, naïve and plucky, like Reese Witherspoon in Legally Blonde. She is beginning a journey that will sometimes be fun, sometimes be difficult, and that will teach her much more than French.

On my left sat a silent phalanx of young men. On the right, a woman with green hair. I gave her a tentative smile, and she smiled back suspiciously.

Madame Schuss was at the front of the classroom where I would normally be. She stacked handouts on the podium, pulled up a presentation and then wrote the following dialog on the board.

Bonjour (hello). Je m’appelle… (my name is). Vous venez d’où? (where are you from?) Je viens de… (I am from…). Enchanté(e). Au revoir.

She gestured for us to get up: Levez-vous!

Knowing how difficult it is to get students moving, I stood immediately. Everyone else sat for a beat, realizing there would be no English. We would speak only French. And we would do so now, to each other, early on a Wednesday morning.

I turned to the student behind me. “Bonjour. Je m’appelle Lyn.” In French class, I’d be Lyn, I decided, and not Professor Millner. “Je viens de Jackson, Mississippi.”

“Je m’appelle Ellen,” she said. “Je viens de Cape Coral.” She had a much better accent than I did and didn’t seem to mind that I was out of place.

Ellen* and I became partenaires for the paired activities, pulling our desks together and sharing a book. Using our basic French, I learned that she was 19. She had younger brothers. She enjoyed reading, something we had in common.

We adored French class and Madame Schuss. Even on exam days, we were eager. And we loved the days our exams were returned. In green pen, beside our A’s, Madame Schuss had written “très bien” and drawn a smiley face.

The theme of Unité 4 was travel. Ellen and I talked about the countries we hoped to visit. Both of us wanted to go to France. I was already planning my summer research trip.

Madame Schuss pulled up a picture of Mont-Saint-Michel. It looked like a castle rising straight out of the water, shrouded in mist. The medieval fortification, in the bay between Normandy and Brittany, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has a Benedictine abbey at the top. Ellen already knew about it.

At high tide, Mont-Saint-Michel is an island. But at low tide, the area around it becomes a salt flat, connected to the mainland. The water level can vary by nearly 50 feet.

“I will go there this summer,” I said to Ellen. She nodded solemnly.

The second semester, Ellen and I registered for the same section of Beginning French II, and we sat together. On the first day, Madame Schuss asked the class about our New Year’s resolutions. I realized what she was doing.

“The future tense!” I whispered to Ellen. “Watch how she is teaching this. It’s brilliant!”

By now, Ellen knew that I was as enthusiastic about ways to teach as I was about learning. Her New Year’s resolution was to read more books. Mine was to make progress on my own book.

We fell in with a pack of other students. All of us looked forward to seeing the activity Madame Schuss had planned for us that day. Occasionally, our zeal disrupted the others, as when we rejoiced at learning the past tense—another milestone.

“My roommate won’t think I’m an idiot anymore!” Caroline French exclaimed. Her last name wasn’t really “French.” We all adopted the surname because no one knew anyone else’s last name. We became the French family, and I was the mother.

In Unité 6, we planned a pretend party and had to decide on food and decorations and flowers and the wording for our invitations. We chose a theme, made a list of supplies, mapped out a shopping route and determined who would do what. Ellen missed that week, and we joked that she would have to do the most arduous errands.

Then she missed a third day. That wasn’t like her. After class, I sent her a text.

“We miss you in class. Are you OK?”

“I’m sorry,” she texted back.

“I had to drop.”

“Oh, no! Darn. I hope the rest of your semester goes well.”

“No I dropped out of school.”

I called immediately from the parking garage.

“You don’t have to tell me why. I’m just calling to ask how I can help.”

But she did tell me. She felt like she was wasting her family’s money, she said, because she didn’t know what she wanted to major in. She liked drawing and acting and singing and language and writing. She wanted to study everything. She sounded depressed.

All in a rush, I tried to tell her that’s what college is about—finding out what you want to do. I told her about the integrated studies major, where you can study a variety of things and design your own degree.

“We can’t afford it.”

I told her there were scholarships and one central site where she could apply.

“I haven’t told my dad,” she said. That was where her head was. She had decided. She told me she’d get a job and come back once she decided what to study. No amount of my persuading could change her reality.

French class went on without her. Cuisine, clothing, healthy habits, music, festivals, telling time. For a while, Ellen and I stayed in touch. She sent pictures of her fabulous fan art, based on illustrations from fantasy books with strong plotlines and excellent reviews. I texted to let her know when there was a French conversation dinner. She texted me a Happy Easter message. She told me she wanted to write a book.

“Maybe it sounds crazy,” she wrote. “Writing a book isn’t crazy,” I wrote back. “Well, actually, it is crazy, but it’s a good kind of crazy.”

I messaged her the schedule to the upcoming Sanibel writers conference, which I knew she’d love. But no car. No money. “I’ll pay half the Uber,” I offered once. I would have paid the full fare, but I didn’t want to make her feel like a charity case.

“Thanks,” she texted back, “but I can’t.” She was finding some writing classes online, though, she wrote.

As teachers, we learn to consider “situational factors,” challenges students face outside of class. Noisy roommates, unreliable transportation. One student told me once that he was driving to class without windshield wipers because he couldn’t afford new blades. Working three jobs is not uncommon for an FGCU student.

It’s easy for a professor to forget these challenges. That semester, I thought about them a lot as I drove to my one job in a solid car on a good night’s sleep because I live somewhere quiet and safe.

The summer after Beginning French II, I went to Tours, France, for a French immersion program. I lived with a French-speaking family and took language classes during the day. I learned the city by renting a bicycle and taking buses and trams—often in the wrong direction. I went to concerts, I grocery shopped, I toured châteaux, I ate foie gras, I watched French movies and listened to French music, and I did all of it in terrible French. In my entire life, I have never felt so vulnerable and idiotic.

The director of the language school placed me in the most challenging class for my level. I’m being kind when I say that my teacher was no Madame Schuss. I’ll call her Madame Agard. She pretended not to understand me when I spoke. More than once, she told me she needed whisky to listen to me. The first time she said it, I went to the bathroom and cried.

The second time, about a week later, I had a comeback. I would like to say I delivered it confidently. But I did not.

Every student was required to give a 20-minute presentation in French. I watched my classmates deliver theirs, and felt complete hopelessness. Arturo brought tears during his story of volunteering with amputees in a hospital in Ecuador the previous spring. After that, I decided that I simply would not give my presentation. I asked Madame Agard if we could speak outside during her smoking break. If she was trying to break me, she had won.

“I can’t do it,” I said in broken French, with a weak voice I hated.

“You will do it.” She blew smoke out of the side of her mouth. I realized that she was going to enjoy it. That, in fact, she would relish it.

“Well,” I said in French. “You will need whisky.”

“Oui,” she said. “Quel type de whisky?” I asked.

“Cognac,” she said.

No self-respecting journalist does a “when animals attack” story, but I did—Des animaux dangereux en Floride—because I know viewers can’t resist them.

Using pictures and videos, I put lipstick on the pig of my presentation and got through it. My classmates loved it. Even Madame Agard forgot herself and smiled once.

Afterward, she cataloged all of my errors for the class, giving more corrections than I could absorb.

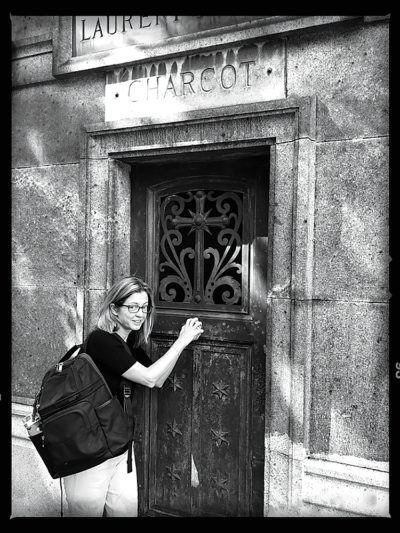

I thought of Ellen most strongly at Mont-Saint-Michel, the place I had told her I would go. My husband and I got there at low tide, climbed up to the abbey and watched the tourists walking on the salt flats. The insistent blaring of a horn warned that the tide was coming. It blared again when the tourists didn’t respond. Within 30 minutes, the water had risen, and we were on an island. Ellen would love this, I thought. I considered snapping a selfie and sending it, but it felt like gloating. She was marooned on her own island in Cape Coral. I didn’t want to make it worse.

In August, when the semester started, I told her she could sit in on one of my classes for free any time she wanted. It would be great, I said, to be in the classroom together again.

“I would love to, but I have no one to take me.”

Checking the bus routes from Cape Coral to campus, I saw that it would take four hours each way. I sent her a bus schedule anyway, and a link to a ride share program that some students use. She didn’t respond. I felt like I had pushed too hard. We were in touch once again, several months later, after Hurricane Irma to check on each other. It has been nearly two years since she left school.

It almost goes without saying that being a college student made me a better teacher. After trying to learn a foreign language, I’m much more sensitive to second-language students. After getting my butt kicked in Tours, I know what it’s like to be at the bottom of the class. I had always been encouraging to my students, but now I realized the value of doing so.

I started giving a survey at the beginning of the semester—an anonymous, optional questionnaire that asks how many jobs students have, how many hours they work outside of school, how much sleep they get at night, and what time of day they have energy dips.

Their answers don’t affect the workload I give them. It’s not my job to make a student’s life easier. But I can fight their inertia with activities that get them moving around the classroom, as Madame Schuss does, and I can give them some work time during our sessions as I circulate and answer questions. Even if I did none of those things, though, just the act of giving the survey makes a difference. When students feel understood, they learn better.

The biggest change I’ve made is with class planning. Before any session, I consider what I want students to learn, as opposed to what I feel like I need to cover. Thank you, Madame Agard.

Writing this article prompted me to get back in touch with Ellen.

“Omg, hi!” she wrote back within an hour. “My Instagram pretty much shows my life for the past year. I did a makeover to it to not drown in complete depression and isolation.”

She said she had connected with lots of writers and readers online. “Lots” was an understatement. On her Instagram were dozens of books she has read and reviewed in the past year, fantasy young adult novels like the one she had told me she wanted to write. She captioned each book post with craft notes. Many of her posts have close to 200 likes each and multiple comments from readers.

I asked how her book was going.

“Well it’s changed completely since last time we talked. I’ve learned so much more about writing and storytelling.”

She had studied YouTube videos and read books on craft. She sent me pictures of some of them, which included two of my favorites, The Deluxe Transitive Vampire and Bird by Bird. I sent her some book recommendations on plot.

She has not returned to school. She has no car. In fact, she has never learned how to drive. One of her goals this year is to learn.

“It’s really terrifying but I have to face my fears.”

I hope she’ll come back to college, and I’ll keep nudging because I can’t help myself. It’s not that I believe a formal education is the be all and end all. It’s that learning alongside others who are learning is an incredible joy. I know that as strongly as I know my own name. It’s why I’m in education. It was most clear in those first minutes of Beginning French I, when I began that awkward conversation that opened up a new world.

*Name changed to protect privacy