These days the youngest student Marina Zoueva trains is 6 years old.

No matter how young a student is, Zoueva knows whether they will gravitate toward figure skating or ice dancing, just by reviewing their physiques and talent. Decades in the field confers a kind of omniscience. Her youngest student, Maria, is a dancer, Zoueva points out, as the young girl arrives for practice one afternoon.

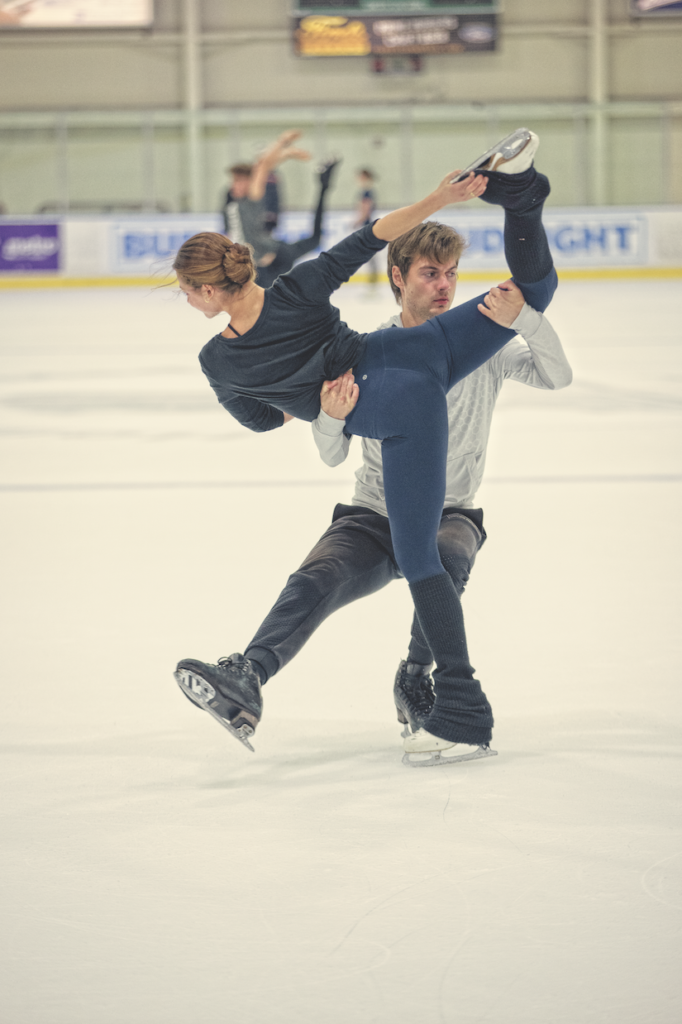

Figure skating, a true legacy sport, has been part of the Olympics since the first winter games in London in 1908, whereas ice dancing—which was derived from ballroom dancing and joined the Olympic winter program in 1976—is the relative upstart. The difference is easy to spot, as ice dancing is less gentle-looking, defined by its acrobatic lifts; light, quick, ballroom-type steps; and the twizzle (three consecutive turns).

Since the 1970s, Zoueva—in her various incarnations as choreographer, figure skating coach and competitive ice dancer—has seen all kinds of talent in both disciplines. She has won medals of her own and guided athletes to Olympic gold.

The legendary coach, who runs the International Ice Skating Academy at Hertz Arena in Estero with her husband Johnny Johns, also a coach, admires 6-year-old Maria for her work ethic, her love of structure and organization. “Talent is nothing if kids don’t work,” Zoueva says.

Perhaps Zoueva sees something of herself in the young dancer; she notes that she too was 6 years old when she began her training on the ice. When is a good age to start? “Three, four,” Zoueva says. “Kids like it—they like the balance between sports and art.” This formulation comes up a lot when Zoueva speaks of her craft: How much of it is sport? How much is art? Matching the correct proportion of each with the right athletes has represented her life’s work.

Zoueva had been teaching skaters since she retired from competition in the late 1970s, first in her native Russia—then the Soviet Union—and since 1991 in the United States.

For 17 years, Zoueva and Johns taught ice athletes in Canton, Michigan, at the Arctic Figure Skating Club, part of the International Skating Academy. But about four years ago, she began to think about a different kind of training, a different kind of life—and not a remotely Arctic one. “I thought about how I could improve the preparation for my elite skaters,” Zoueva recalls. “Where could my athletes train year-round and exercise outdoors?” With those thoughts in mind, she sought to develop a wholly different type of training environment. She wanted her skaters and dancers to be able to harness the power of nature, from the sun, from the sea—and to be able to test their bodies in a range of unlikely yet complementary sports. The veteran coach believed a new regimen might give her competitors an edge on rival athletes who trained solely indoors in a more conventional way. That’s how the nearly 8,000-seat Hertz Arena—the home of minor-league ice hockey team Florida Everblades—became the new base for her International Skating Academy. “I moved everyone here,” she says. “The coaches and the skaters.”

The geographic move has called for adjustments in the athletes’ mindsets, but soon the ice skaters and dancers were playing beach volleyball every Sunday and canoeing and kayaking on the Estero River. Soccer, tennis and cycling are sometimes part of the regimen. But it was on the water where they learned about continuous motion—and developed a fresh type of discipline. “They would complain,” Zoueva says, laughing. “You can’t stop, you can’t rest. You have to paddle back. In the gym, you do as much or as little as you want. You can stop anytime, basically. It’s not really natural.”

As for Zoueva, both the climate and the culture suit her. She doesn’t miss attending cultural performances in Michigan and then searching for her car in the frigid evenings. “The winters were difficult. It wasn’t a pleasure to go in and out,” she says. Southwest Florida offers her the opposite: After an event at Artis—Naples with the Naples Philharmonic—which features Russian-born conductor Andrey Boreyko, a fact that makes Zoueva proud—she would marvel at the sultry nights. “It’s paradise,” she says.

Zoueva has guided some of the world’s most elite athletes to Olympic medals. Having coached future Olympians since they were preteens gives her a unique insight into who they are, what they are on the ice. Early in her coaching career, she worked with the Russian figure skating pair Sergei Mikhailovich Grinkov and Ekaterina Gordeeva, who went on to capture gold medals at the 1988 and 1994 Olympics.

But it was her collaborations with ice dancers in the 21st century that finally put North America on the map in a discipline that had been recognized at the Olympics for just a few decades. Because the Olympics does not include solo ice dancing in competition, the chemistry of the pairings defines the sport. When they medal, the couples become iconic.

At the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver, Zoueva’s Canadian pupils Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir tangoed seamlessly on the ice and dazzled the judges and the crowd with the shapes they created with their bodies in motion. They stunned the world when they became the first North American gold medalists in ice dancing. “Tessa and Scott are art on ice,” Zoueva says. “When you watch them, you feel the love. Their chemistry is key. I emphasize this side of them, to bring out the best in them.”

Zoueva struck gold again, in 2014, when her dancers Meryl Davis and Charlie White—the top rivals of Virtue and Moir—became the first Americans to capture the gold in ice dancing, at the Winter Olympics in Sochi (the pair had notched the silver in Vancouver). Zoueva had composed choreography for White when he’d competed as a single, but he won fame as part of a pair.

In 2014, Davis and White danced with arresting urgency, as in their free program set to Music of the Night from the Broadway show The Phantom of the Opera. “I saw so much sport in his spirit—he’s an athlete,” Zoueva says. The fact that White had a background as an ice hockey player was not lost on Zoueva; she immediately grasped the value of an interdisciplinary approach that would later inform her coaching in Southwest Florida.

The dancer inspires not only the dance. White’s personal qualities helped advance the form itself. On the ice, he at once radiates muscularity, charisma and theatricality, and his crown of blond ringlets gives him a presence like no other.

Between 2010 and 2014, Zoueva contributed to an important evolution on the ice: “Before Charlie, ice dancing was more art, but with him there was a balance between art and sport. It’s the total opposite of Tessa and Scott. For Meryl and Charlie, it’s about power, speed, emotion. Together, they’re like a hurricane—very impressive, no question. Men started to ice dance after seeing what Meryl and Charlie could do.” Davis and White grew up together as kids in Michigan. They have been training and competing since 1997 and are the longest lasting pair in ice dancing.

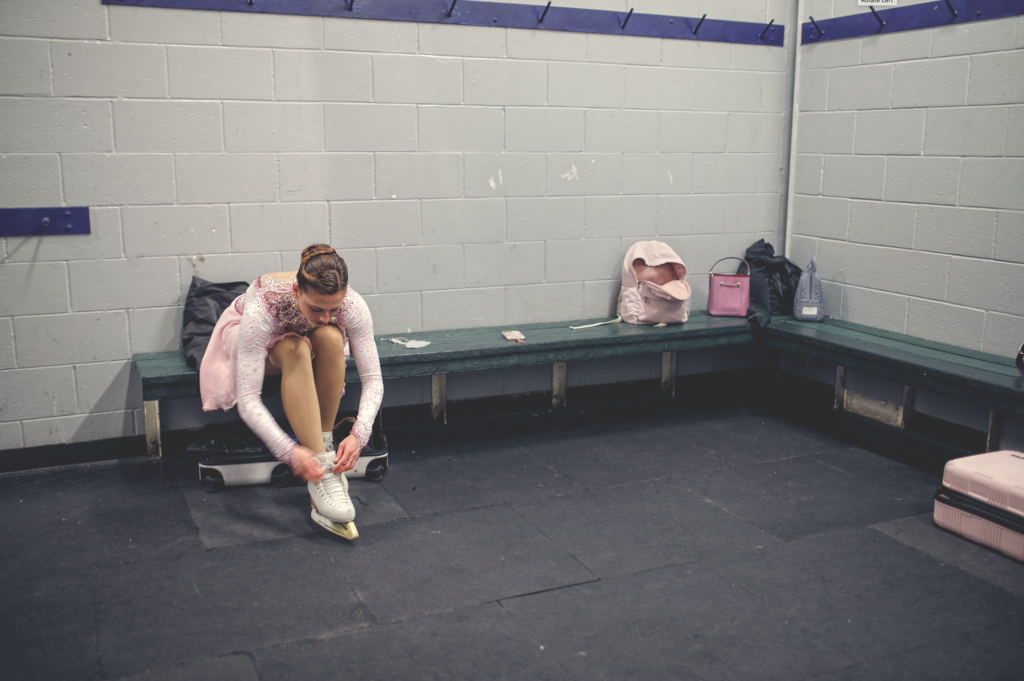

For at least one athlete, the move to Naples was a homecoming. Nicole Kelly was raised in Fort Myers, spent a year training with Zoueva in Michigan, and followed her coach back to Florida. The two-time national champion in solo ice dancing will likely compete at the 2022 Winter Olympics as part of the Turkish delegation, since her partner Berk Akalin is from Turkey. “She’s a super artistic girl,” the coach says, and describes her keen admiration for Kelly’s interpretive skills: “Her body can explore the music, which is one of the most important things in ice dancing. She hears any kind of music and naturally moves in the right way, whether it’s pop, hip-hop, classical or blues.”

As for her own gift, perhaps more than any coach on the scene, Zoueva took the measure of the gifts of others so they were able to glide, spin and twizzle their way to Olympic gold. Now, if she manages to achieve this in the subtropics, she will be on the map in a whole different way.

Photography by Brian Tietz