On a clear and sunny Thursday morning, three shrimp boats arrive early at the docks on Fort Myers Beach. They tie off and wait their turn to unload at the shrimp house owned by Erickson & Jensen, which has been on San Carlos Island since 1965. The shrimp house is a cavernous structure with plywood floors and an open ceiling. On this particular morning, an industrial fan in the corner blows hot air and a radio plays Savage Love by Jason Derulo. The cries of gulls and the clink of boat rigging can be heard from the wharf. Inside, the air smells of fresh shrimp, the scent of the sea. A small crew of day-pay workers mill around, smoking and looking at their phones. They are mostly men, their skin tanned and their faces lined from years spent near the water.

At the center of the room stands Anna Erickson. She’s dressed in a pair of green khaki shorts and a Grateful Dead T-shirt, green Crocs on her feet. Her brown hair is tossed up in an easy bun and her blue eyes snap as she calls out directions in a no-nonsense voice. “OK, focus, focus. These four and then done,” she says. Yesterday was Erickson’s 34th birthday party, and the crew this morning is running a little slower than usual.

A conveyor belt leads from the shrimp house to one of the shrimp boats tied up at the dock outside. Purple mesh bags of pink Gulf shrimp start sliding in. At Erickson’s direction, a man pulls on a pair of gloves and starts stacking the sacks of shrimp on a palette. Erickson moves to a counter against the side wall, and inspects a sample of shrimp coming off the boat. She weighs them, counts them, calls out numbers and makes notes on a clipboard. “OK, we’re good to go,” she says.

The palette is forklifted out of the shrimp house, and Erickson picks up a broom and starts sweeping out the dried shrimp legs that have scattered across the floor. One of the guys off the shrimp boat comes riding in on the conveyor belt. He looks like a young Willie Nelson. He has his arms outspread and he’s grinning like, “Does anyone see this?” Erickson tells him yesterday was her birthday, and he hops off the belt and gives her a big hug, “Well, happy birthday,” he says.

“We consider ourselves a shrimp family,” Erickson tells me later, talking about her crew of unloaders, captains and shrimp workers on the docks. “We love each other.”

Today, there are only two shrimping companies still on San Carlos Island, Erickson & Jensen and Trico. Erickson & Jensen is the larger of the two, with 12 boats, diesel tanks, a ship’s store and an unloading house.

The Ericksons have been shrimping for four generations. The youngest generation is made up of Erickson and her older sister, Hally, who lives in Brooklyn and works in New York’s art industry. That means someday Erickson will take over her family’s shrimping business. In an industry largely run by men, she’s a rarity. “But I run circles around the dudes, so that’s no problem for me,” she says, with a laugh.

The rush on Gulf pinks—called pink gold in shrimping lore—began in 1949, when shrimp were discovered off Fort Myers Beach. Erickson’s great grandfather, “Big Grandpa Carl,” was the first in the line of his family shrimping business. He’d been a fisherman in Montauk, N.Y., and he brought the family boat, the Malolo, down to the shrimp docks. He joined the ranks of other shrimpers who plied Gulf waters throughout the 1950s and 1960s. In its heyday, several shrimp packing houses served the shrimping fleet.

But in the 1970s, the shrimping industry in the United States began to face serious challenges. Rising gas prices took a chunk out of profits, and in 1976 the Mexican government closed the Mexican shrimping grounds to foreign shrimpers, decreasing the area U.S. boats could shrimp. At the same time, the U.S. began importing farm-raised shrimp from overseas. By 2009, half of the shrimp eaten in America would come from foreign farms.

In the 1980s, threatened with increasing costs and challenges from overseas-produced shrimp, the local shrimping fleet downsized from close to 1,500 boats to about 500 boats. With the reduced number of boats on the waterfront, businesses that catered to the fleet also disappeared—net shops, supply houses, welding workshops and maintenance yards. At the same time, tourism was on the rise, and Fort Myers Beach began transitioning from a small shrimping community to a vacation destination. In the early 2000s, increased environmental regulations like turtle excluder devices (TEDs) piled on more costs and reduced hauls. By 2013, more of the San Carlos Island packing houses had closed, and today the local shrimp fleet is down to about 40 boats.

Still, some independent shrimpers and larger companies like Erickson & Jensen survived. For those who weathered the storms, the industry continues to pay off. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission estimated the dockside value of the Florida shrimp haul in 2018 at $48.9 million, higher than other top commercial fishing products like grouper, mullet, stone crabs and blue crabs. Unlike other fisheries categories, shrimp are rarely considered overfished.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) currently lists the pink Gulf shrimp population above target levels. Gulf shrimp have a short life span—less than two years—so they’re often considered an annual crop. And Florida shrimpers must abide by federal and state laws when harvesting from the Gulf, which keeps the population at sustainable numbers.

Between 1997 and 2016, the Florida Department of Agriculture estimates that more than 220 million pounds of shrimp were caught in Florida waters. San Carlos Island offloads more pink Gulf shrimp than anywhere else in Florida—something that’s been celebrated for more than 60 years each March when the local Lions Club traditionally throws the Fort Myers Beach Shrimp Festival. This year, however, the festival has been canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic.“The industry is still strong,” says Tracey Gore, former mayor of Fort Myers Beach, whose husband owns his own independent shrimp boat, the Lexi Joe. “There are fewer boats than 25 years ago, but it’s still a strong industry impacting local jobs. Commercial shrimping is treasured locally, and these men are proud of their work. You want to meet some real workers, go down to the docks and watch those guys.”

Gore, who grew up on the beach, remembers telling her mother that she was dating a shrimper. “Just so you know, his hands are pretty greasy from working on the boat every day.” Her mother’s response? “I’d rather you date a man with dirty hands that works than a man with clean hands who doesn’t.” And, anyway, Gore’s soon-to-be-husband came from good stock: his father was a doctor and his family lived off McGregor in Fort Myers. Shrimping, he’d realized, could make a very good living.

Typically, Erickson & Jensen’s fleet spends the summer months from the Fourth of July to Halloween shrimping off the coast of Texas. The company owns an unloading house, a small ship’s store and fueling dock in the fishing community of Aransas Pass. But in 2020, the fleet decided to stay close to home. Many of the Texas plants, where the boats send their shrimp, were closed because of COVID-19, and the government-issued maps that show shrimp populations in the Gulf were suspended because of the virus. Still, shrimpers say it has been a good year. Each of the last three years, Erickson & Jensen’s boats offloaded more than a million pounds of shrimp at the San Carlos Island docks. The company anticipates the same numbers this year.

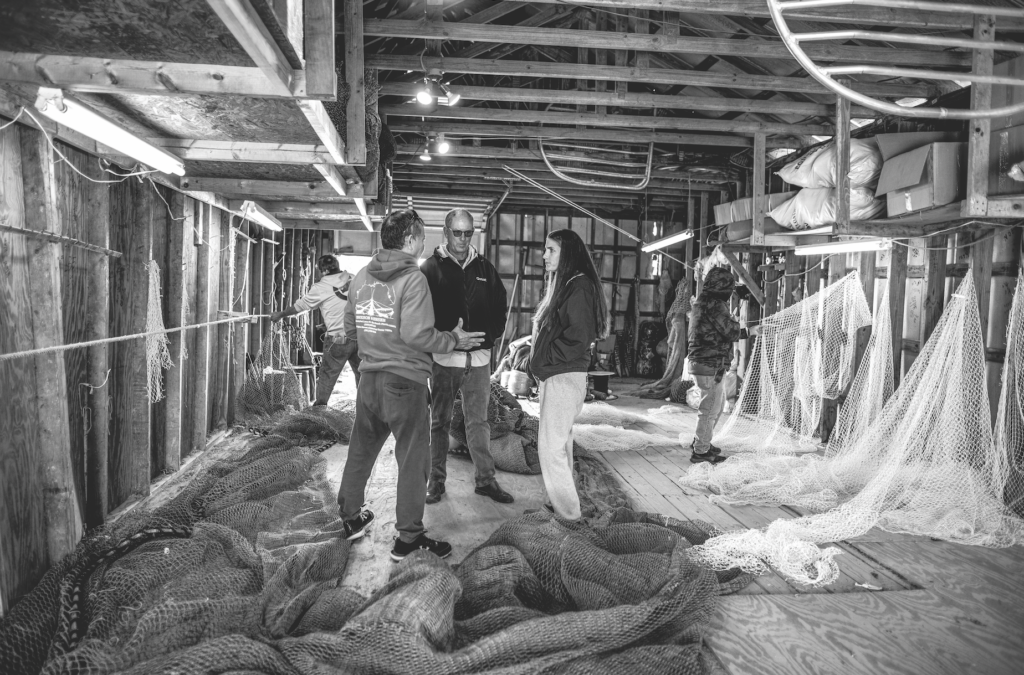

Joanne Semmer, president of the Ostego Bay Foundation—a marine science research and awareness organization on Fort Myers Beach—grew up beside the shrimp docks and has been closely connected with the shrimping industry her whole life. Now, she leads the weekly working waterfront tours. “When the boat captains are down on the docks, they’re hot and sweaty, they’re shoveling stuff, they’re working on mechanics,” Semmer says. “But that all washes off when they go home.”

And that home? It’s often paid for with cash, a new truck—also bought with cash—parked in the driveway.

Shrimping faces the same struggles as other primary industries like farming and ranching. It can be well-paid, but young people are steered away. They’re told to go to college and work in an office instead. Though Erickson heeded the call to go to college—she went to Florida Atlantic University, where she studied business—she ignored the part about working in an office. Erickson grew up by the water and used to play hooky whenever she could to go down to the docks. Some of her favorite characters over the years have included Rusty, a shrimper with a big red beard who brought her a rose every time his boat docked, and Thomas Mitchell, an old shrimper who passed away last year in his 90s. “Which is really old for a shrimper,” she says. “You know what salt water does to people—and anything, really. It wears you down.” Mitchell used to come to the docks every day after he retired, decked out in gold nautical jewelry. He liked to reminisce about the glory days, when fuel was cheap and farm-raised shrimp hadn’t hit the market. “When shrimpin’ was pimpin’,” he’d say. Mitchell was the man behind the necklace Erickson still wears, a solid-gold shrimp as big as her thumb. Her pride and joy, she calls it.

Shrimpers are a notoriously hard crowd—hard working, hard partying, hard living. Erickson seems to have figured out the exact right balance of sweetness and toughness to keep her crew in line. “A lot of these people have known me my whole life,” she says. “They know that whatever I say goes. When I say something has got to be done, there’s no doubt about it. Everyone just falls into place.”

Her father, Grant Erickson, says she’s not intimidated by anything. “She’s a bright girl, she’s got such an outgoing personality, and she adapts well. This bunch of edge-of-society people that we deal with down here, they love her.”

Erickson’s house off McGregor is filled with gifts the shrimpers have given her—seahorses, scallop shells. On the docks, she likes to read what she calls jail mail—letters home from shrimpers serving time. The letters often touch on the same themes: the men are missing their shrimp family and they can’t wait to get back to the sea. “Nobody’s perfect,” Erickson says with a shrug. “But, they’re my people, and I love them.”

She affectionately calls the old shrimpers who hang around the docks barnacles. There’s only a handful of them left. When one of them passes, she holds a memorial service at the docks with a special rock shrimp salad. Rock shrimp are famously difficult to clean, so the making of the salad becomes a kind of labor of love. The ratio of rock shrimp to pasta depends on the prominence of the man who died. Recently, when one of the old-time captains who went by the nickname Roach passed on, Erickson made sure he got an honorable 60-40 rock shrimp-to-pasta ratio. At his memorial service, she took up the megaphone and called out, “All right, everybody, raise your cigarettes for Roach.”

Erickson envisions her future continuing in the shrimp industry, working within the company where her father, grandfather and great-grandfather worked before her. She has ambitions to move some of the business online, to open out-of-town markets to pink Gulf shrimp. And she hopes to make progress in raising awareness about the value of Gulf pinks. “People don’t understand the difference between a wild-caught shrimp and a farm-raised shrimp,” she says. “They think shrimp is shrimp. But once they try one of our shrimp, they realize there’s nothing like it.”

Though Erickson’s father is still hands-on with his company, he’s preparing for the day when his youngest daughter will officially take over. “I’ve added to what my father and grandfather had established, and Anna’s going to put her special twist on it,” he says. “So, onward we go.”

As for Erickson, she’s happy to be on the docks each day, working at the center of it all. “This is my world,” she says. “I love it here.”