The joy of wine is that it’s ever-evolving, a continual discovery of beautiful things to drink. For Peter Rizzo, his 5-year-old shop, Natural Wines Naples, is a new, exciting chapter in his 30-year career in wine. A former importer, he has a keen eye for trends. Trips to New York City and Los Angeles to visit his daughters were spent exploring the natural wine shops and bars popping up throughout the cities. With his eyes opened to the energy and nuances of natural wines, he founded the region’s first shop dedicated to the winemaking movement in 2016.

Although there is no official definition for natural wines, the term usually refers to those made in a low-intervention style, meaning no pesticides in the vineyard or additives to the wine. Fermentation is done with native yeasts, and little to no sulfur is added. Rizzo calls these wines “the most authentic expression of what wine is,” noting that they speak to a wine’s terroir, or sense of place.

Natural winemaking is hard to scale, and production is often tiny and highly allocated. Rizzo may only receive a couple cases from sought-after producers for the entire year. However, one special cuvée he carries regularly is the Queen of the Sierra red blend by Forlorn Hope, based in Northern California, which Rizzo calls “exemplary of the creativity of the natural wine movement.”

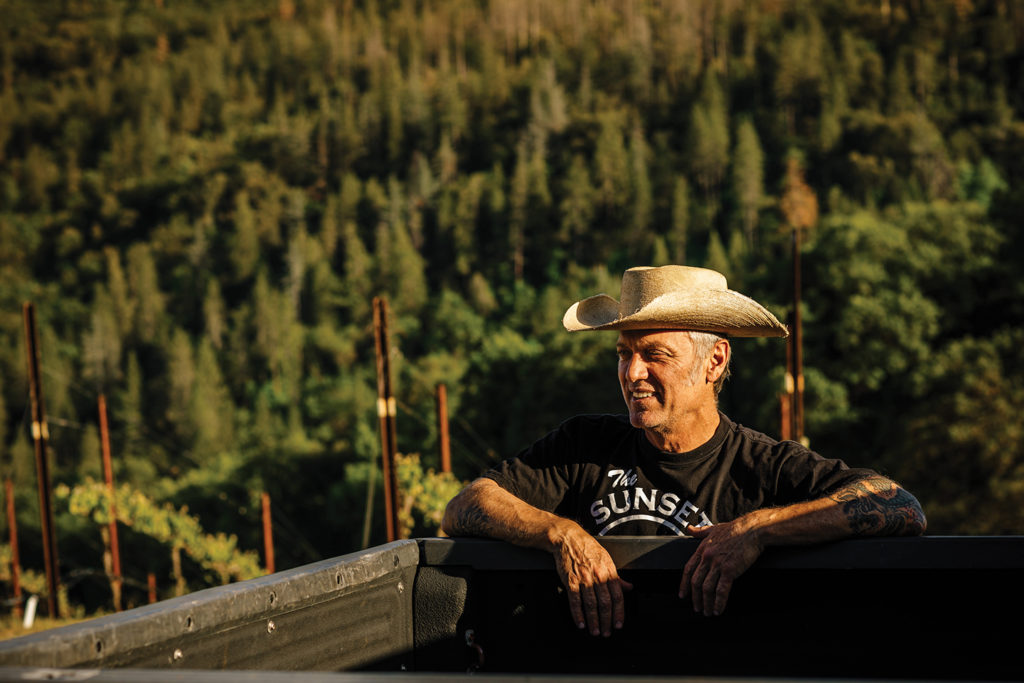

Forlorn Hope’s winemaker, Matthew Rorick, grew up skateboarding in Southern California, and after a stint in the Navy, intended to pursue a degree in literature. He lived with his grandfather at the time, who had amassed a collection of prized Bordeaux and Burgundies during his travels. “He taught me to cook and would take me into his cellar to pick bottles of wine that might go well with what we were cooking that night,” Rorick says. Intrigued by the interplay of food and wine, Rorick kept learning about the craft and, with some nudging from his grandfather, transferred to the University of California, Davis’ enology program.

Upon graduating, he set off on a global exploration of winemaking regions. During his travels through California, Chile, New Zealand and South Africa, a common thread emerged: He wanted to produce wines that didn’t rely on the corrective chemistry that is common in modern winemaking. But, to grow grapes in an environmentally responsible fashion without additives would require his own vineyard and an all-estate wine program.

While working with growers in California as he saved up to purchase his own vineyard, Rorick came across the Sierra Foothills, specifically Calaveras County. “I was kind of blown away,” he says. “It’s this vineyard planted on limestone. I don’t think I was even aware that there was limestone in California, outside of a couple of very specific spots.”

Part of the renowned soils in top French wine regions, including Burgundy and Champagne, limestone is rare in California vineyards. The Sierra Foothills have what Rorick calls an alpine growing environment: The condensed growing season results in less disease pressure, and cold nights preserve the acidity in his wines. In the winery, he eschews chemicals and most additives, except for minimal amounts of sulfur, which protects against oxidation and microbial issues. New oak—which imparts additional flavors—is never used, allowing the fruit to shine.

Instead of focusing only on popular, proven varieties, Rorick plants grapes that are thought to have existed in California pre-Prohibition. Queen of the Sierra, for example, is a blend of several varieties, including tannic mondeuse and robust trousseau noir, as well as more familiar grapes like tempranillo and zinfandel. The wine exhibits tons of texture, with dark red and black fruit, spice and an earthy savoriness. “Each variety contributes to the character of the blend, but you also want to minimize the individual variety and let the site take centerstage,” Rorick says.

With the merging of current winemaking trends and a reverence for history, Rorick’s wines are a nod to the past. From the varieties he cultivates to his vinification techniques, which bypass many modern winemaking tools, he is part of a movement that wants to reclaim wine in its purest form.