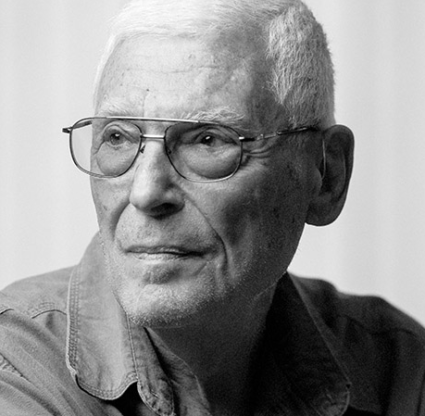

Kevin Rambosk is meticulous. His shirts always seem crisp, even three-quarters of the way through the day when most people would be a bit wrinkled. His hobbies include home repair and antique car restoration (usually classic American muscle), both of which require attention to detail. Even when a picture is hung on the wall, everything must be precise.

“I can’t hang anything without him measuring,” his wife, Pat Rambosk, jokes.

So it seems a bit hard to believe that being Collier County’s sheriff wasn’t always part of a grand plan he has chipped away at over the past 30-plus years. His only goal was to be in public service ever since he started volunteering as a 14-year-old HAM radio enthusiast for the civil defense—what we’d now call emergency management.

Growing up in New Jersey, Collier County wasn’t even on his mind. But when his new wife’s parents retired to Naples, the couple figured they’d eventually wind up there, too. And then Pat decided she’d rather not wait.

“So I got a letter in the mail saying I had an interview with the City of Naples police department,” Rambosk says. “I hadn’t applied. So I told my wife about it and she said, ‘Oh, I applied for you.’”

That was 1978. Collier County didn’t have a third of its current population, and most of the gated communities and shopping complexes that make up the coastal part of the county were swamps or fields.

Now it’s developed heavily past Interstate 75 and expected to double its population in the next 30 years. The pace and density of development is one of Rambosk’s biggest concerns going forward as he begins running for his third term in office. It’s serious enough that his department employs its own growth management division rather than rely on the folks who work directly for Collier County. He says it’s because those folks have enough to worry about in terms of zoning and building laws. But you get the sense he also wants to be able to exert his own control over the process.

His demeanor comes off as commanding but not domineering, something longtime Naples City Councilman and former Mayor Bill Barnett says has been the case from the beginning. Rambosk served as a police officer, chief of police, assistant city manager and finally city manager of Naples before joining the CCSO to head its organized crime division in 2003. “I’ve known him since I got to town. He’d only been on the police force for a few years when I joined the city council in 1984. The great thing about Kevin is that he’s the same guy he always was. Rational, calm, in control. I don’t think I’ve ever seen him be irrational about anything. He’s always coming at a problem from the position of, ‘How can we solve the problem?’”

It’s that perspective that makes his push for crisis intervention team (CIT) training for his deputies and correctional officers seem obvious, even though much of the country has yet to follow the lead. When he got into office in 2008, Rambosk realized one of the biggest issues facing law enforcement was dealing with people who have mental health or addiction issues. Often these situations escalate rapidly, causing untold damage. And especially in a county like Collier, which allocates no governmental funding for intervention or treatment services, the responsibility to deal with the problem almost always falls to law enforcement.

“The largest treatment facilities in the country are county jails,” Rambosk says. “But those places aren’t the best places to treat people. So our goal has been to redirect people with mental illness to people who can help them.”

To do that, first his deputies needed training. Over the past few years, Rambosk has pushed to have the more than 1,000 sworn members of his team spend the 40 hours in the classroom needed to become CIT-certified. Collier County is the only law enforcement department in the state and one of very few in the country to reach that level. And Rambosk isn’t finished.

“Now the goal is for the support staff to have that same level of training,” he says.

The goal is partly self-centered. Sending fewer people to jail who need treatment saves money in the long term. And the better-trained deputies are, the less likely an incident escalates to violent levels. But Scott Burgess, CEO of the David Lawrence Center, one of Rambosk’s biggest partners in this endeavor, says even the obvious benefits haven’t convinced that many departments around the country.

“I’ve been here 18 months and it’s been amazing the partnership that Sheriff Rambosk has built,” he says. “I came from the suburban Chicago, and we met with significant resistance in trying to get programs like this off the ground. It’s just not an idea that is naturally embraced by law enforcement who tend to think that their jobs are just to put away criminals.”

Although the biggest dips in the crime rate happened in the early 2000s, when Rambosk held several senior positions in the sheriff’s office, crime rates are down about 17 percent since he took over in 2008. But putting away criminals isn’t Rambosk’s primary objective. If he’s doing his job right, there aren’t that many to deal with. Throughout a recent conversation, he mentioned several times early criminologist Sir Robert Peel’s nine principles of law enforcement. Even though they were written in 1829, Rambosk especially points to the first three as a guiding light for what he’s trying to accomplish. To paraphrase, Peel says the goal is to prevent crime before it happens. The only way that can happen is if the public approves of law enforcement methods that will cause the populace to voluntarily comply with laws.

Granted, implementing this strategy was a lot easier in Naples, with a population of about 25,000, than it is in Collier, where he needs to protect about 350,000. But he’s always looking for ways to increase the feeling of partnership between the community and his department. He’s started open gym nights at local schools, created a 5K run and Hot Summer Nights block parties. He estimates about 40,000 kids a year participate in some CCSO program.

He encourages his deputies to be involved in the community through civic groups, to be immersed in the various organizations that create the backbone of Collier County. And he leads by example having served on boards from the Greater Naples Chamber of Commerce to the Shelter for Abused Women & Children to the Boy Scouts.

Pat Rambosk, who is the city clerk in Naples, says her husband’s job can be a little all-consuming. With both of them in public service, and Kevin in increasingly important roles, finding time for each other and their children, both adults now, was challenging. It’s hard to turn off when your job is ensuring the safety of an entire county. That’s why if you see them out for dinner, it’s likely in Fort Myers or elsewhere in Lee.

“If he’s in Collier County, he’s still working even when he’s not on the job,” she says.

And he’s not planning to stop any time soon, even as he hits his 60s. Rambosk has never seriously been challenged in an election, and no one has stepped forward so far to challenge him. While he won’t make any commitment to how long he’ll stay in office, it’s hard to imagine him not running again in 2020 if he’s successful next year. There’s still a lot left for him to do, from continuing the implementation of his community safety plan to revolutionizing emergency response.

“I need the challenge,” he says. “I will always be in public service somehow. To me, it’s fulfilling to do this day to day.”