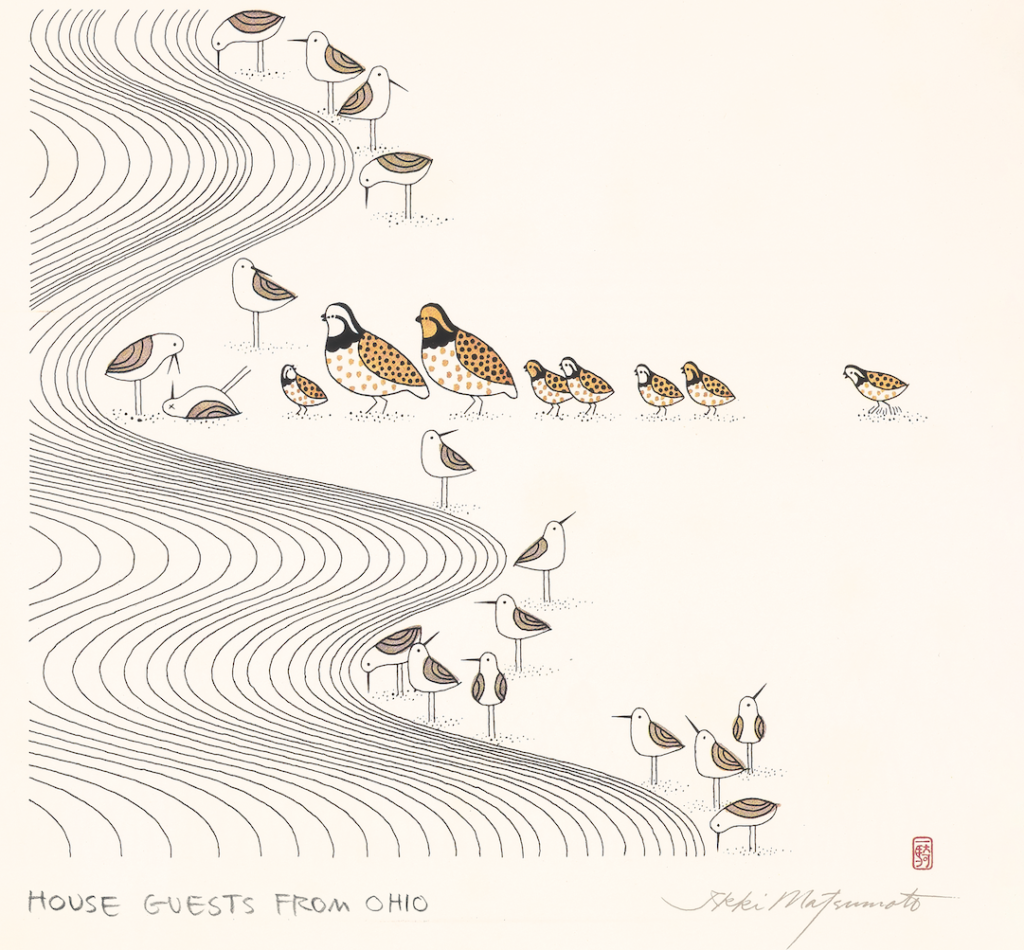

Artist Ikki Matsumoto’s whimsical depictions of Sanibel’s wildlife have become like emblems for the island. His Sandpiper pieces, inspired by the birds flocking to the receding tide, pecking at coquinas and scurrying away from the incoming waves, can be found in galleries, businesses and homes across the world. Those needle-beaked birds earned him great acclaim (Ikki was tapped by Nancy Reagan to create an Easter egg for the White House after gaining recognition for the Sandpipers), and they only represent a fraction of the impact he and his wife, Polly, had on Sanibel. Together, they helped shape the island into the colorful place that it is today.

His work, along with resear-ched history and personal stories about his family’s life in Southwest Florida are chronicled in Captivated: The Art of Ikki Matsumoto. Released last fall, the book, which recently won the Richard E. Rice Gold Medal Prize for Visual Arts from the Florida Book Awards, marks the first time the prolific artist’s work has been compiled into a published collection.

Considering the place the Matsumotos hold in island lore, it’s fitting that the project would be born on its sandy shores. A few years after Ikki passed away in 2013, Steve Saari, a creative director and fellow Sanibel resident, called upon Polly and the Matsumotos’ daughter, Amy Matsumoto Urich, to help create a book to span Ikki’s artistic career. “My wife Karen actually said, ‘I wonder why there isn’t a book of Ikki’s work?’” he says. “I called Polly shortly after that and got the idea and ball rolling.” Flipping through the pages, you see how the island developed—and, in many ways, blissfully didn’t develop—with the Matsumotos since their arrival in the ’70s. For anyone who grew up in this area, the lighthearted, delightful appeal of Ikki’s wildlife illustrations serve as a reminder to stop and appreciate our environment. His ability to translate the whimsy of our shores onto paper draws so many of us in. It’s also a quality that we seem to need and long for more these days. That’s in part why earlier this year, I met with Amy and Saari to see the island through Ikki and his family’s eyes.

Driving over the Sanibel Causeway, I can imagine a young Ikki sitting at the Lighthouse Beach with Amy as a child, sketching out plans for a Sandpiper piece. “We lived off of those Sandpipers,” she later tells me as we’re standing by the beach. “That’s what fed us.” Though each of the Matsumoto clan eventually moved away from Sanibel, the island remains a big part of their lives. Amy often visits with her own kids, bringing them to art galleries and to the beaches to look for coquinas in the sand, like she did with her dad as a child. “Dad would make coquina soup,” she says with a laugh. “No one else would eat it, but we loved helping him collect them.”

Amy, Saari and I start our journey at the new campus for BIG ARTS, an organization that Ikki and Polly helped launch in the late ’70s with a handful of fellow artists, who would meet at each other’s homes and host events wherever they could. “But then mom found the cottage,” Amy says. That cottage became the foundation of BIG ARTS, which the arts group eventually built around to include more spaces to showcase. In 2019, the cottage was torn down and a new facility was constructed, fully equipped to host large-scale performances, exhibitions and an assortment of art classes for the community. “It all came from that idea back in the ’70s,” Saari says. “They said, ‘Let’s get something going here, let’s get organized and let’s get together.’”

That was in the early days when the family first moved to Sanibel. After a successful, albeit creatively unfulfilling, 16-year career in advertising in Ohio, in the mid ’70s, Ikki and Polly decided to leave the winters behind and pursue art full time. They drove up and down the coasts of Florida and settled on Sanibel with their three kids. “If you live on Sanibel Island, there’s inspiration everywhere you turn—you just have to look,” Saari says. “As an artist, it spoke to Ikki’s soul.” They moved down in 1975, just after Sanibel had been incorporated as a city with rules set in place to preserve nature and prevent urbanization. It was also a time when many islanders wanted to maintain a cohesive slate of white and neutral-toned buildings. But, the Matsumotos and other locals saw a brighter, more eccentric future for the coastal town.

Just a short walk across the parking lot from BIG ARTS, we enter the Sanibel Historical Museum and Village to see their first family home on the island: the Burnap Cottage, which was built in 1898, and has since been moved around the island, expanded upon and ultimately restored to its original form. Amy walks through the main room, pointing to a spot on the floor where Ikki would lay out prints of his work; a window that used to lead to her shared bedroom with her brothers, back when the home had a second-story addition; the straight line between the front and back doors that created a rug-rustling draft when the breeze came through. “It looks about the same as I remember it,” she says, walking over to a display with photos of Esperanza Woodring, the well-known fishing guide who lived next door to the Matsumotos on Woodring Road in the ’70s and ’80s. “She was like a grandma to me,” Amy says.

As the youngest Matsumoto child, Amy spent most of her life on Sanibel, often helping her parents in their gallery and tagging along at art shows. In the rearview mirror, I can see her face light up as we drive along Tarpon Bay Road, one of the island’s streets where she once roamed. Her eyes crinkle to reveal a smile behind her mask, as she reminisces about her family’s time on the island.

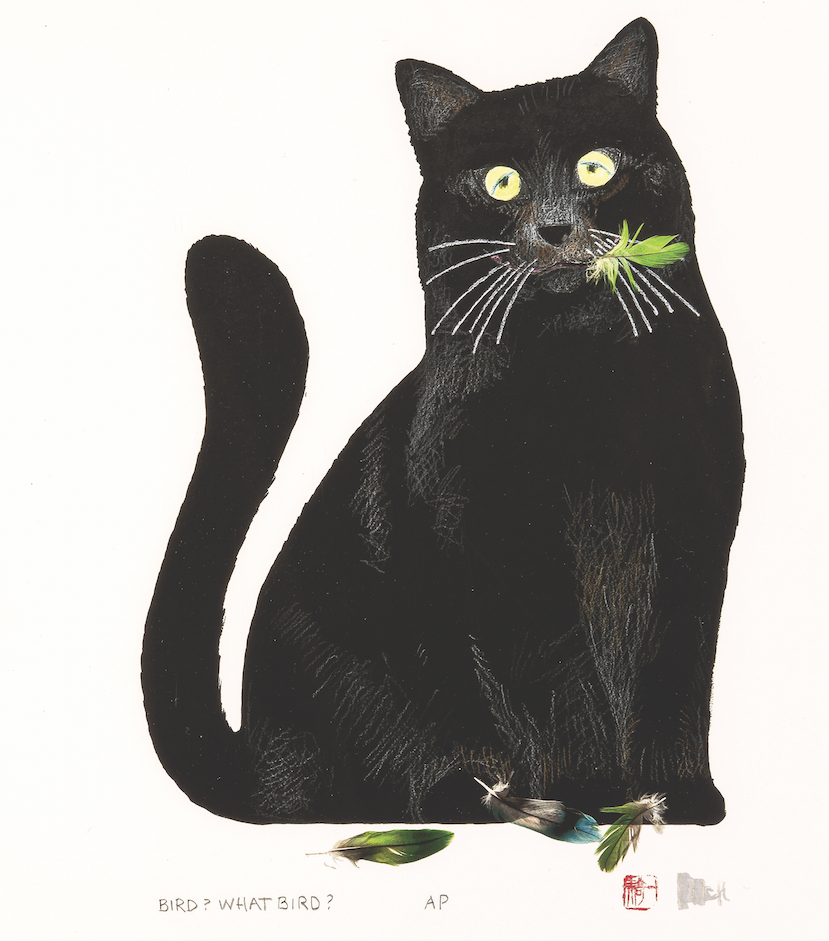

“You asked me about a place on the island that inspired him,” Amy tells me, as we’re driving toward our next stop, Tower Gallery, the co-op that her parents helped form in the 1980s. “Well, I would just say it’s the island.” That is evident in the pages that fill the book she curated with Saari, which include illustrations such as Girl on Swing, which depicts Amy playing with butterflies beneath the trees at their family home in Ohio before moving to the island; Bird? What Bird? that shows their family cat Chica looking guilty with lovebird feathers protruding from her jaws; and Jump for Joy, a technicolor, exuberant depiction of the Gulf’s playful dolphins. One of the last pages in the book shows an unfinished sketch of three burrowing owls perched on a branch, a piece Ikki worked on in the final days of his life. Much like the area’s wildlife, moments with Ikki’s family served as great inspirations for his work.

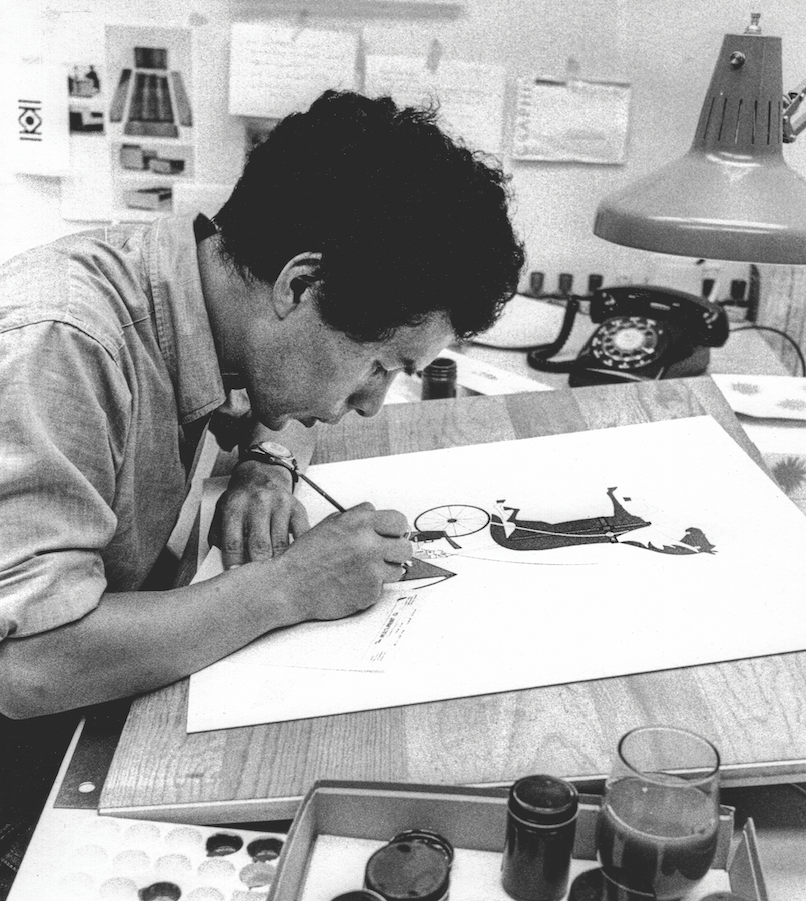

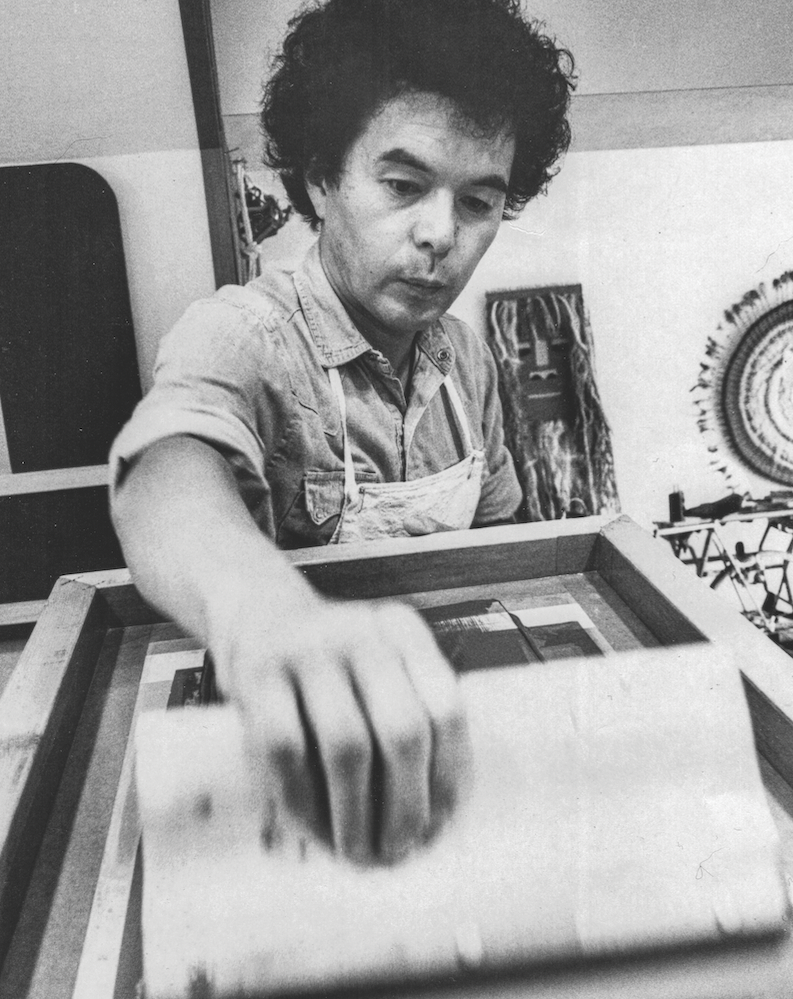

Son of famed Japanese cartoonist Katsuji Matsumoto, Ikki was destined for an artistic life. He left Tokyo in the mid ’50s to join his brother at an art school in the U.S., where he met fiber artist and his soon-to-be wife, Polly Adamson, and his mentor, renowned illustrator and conservationist Charley Harper. Known for stylized wildlife prints, Harper taught Ikki his motto to “never count the feathers in the wings; just count the wings”—the Cincinatti-based artist’s sentiment for describing his style, which he called minimal realism, creating distinct shapes and textures that tell a story without excessive brushstrokes or details.

Around 11 a.m., we pull into the gravel parking lot and walk up to the robin’s-egg blue building, with periwinkle fencing that Polly painted and Ikki decorated with fish cutouts and silhouetted aluminum panels in a sunset design. “The colors were controversial, right?” Saari asks. “Oh God, they about died,” Amy responds, with a laugh. “The whole island was white and beige, but then mom painted this purple, blue and green.” Other locals tried to get her to repaint it, but Polly didn’t budge. “Five years later, all the buildings were painted blue and orange,” Amy says. “She was an influencer.”

Once in the gallery, artist Katie Gardenia, who also founded the Bubble Room restaurant, shares her own memories of Ikki. “When we would do an art show together, I would have to tell him to stop telling me stories because I couldn’t stop laughing,” Gardenia says. She’s working the front desk at the artist co-op, which once served as Ikki and Polly’s studio gallery. Polly, a talented artist in her own right, represented Ikki and managed his flourishing career. The Matsumotos were a close-knit family, and when Amy wasn’t at school, she’d often be in the gallery with her parents. Saari remembers visiting and seeing a young Amy stringing shells and beads together for the jewelry she would sell at the shop. The gallery still sells prints and originals of Ikki’s work. Gardenia points us to an upstairs closet where she’s been holding an Ikki print a fellow artist found for Amy to pick up. The cormorants’ colors have faded with time, but Amy says it’s nothing she can’t remedy with a trip to her printer for a color correction. Having spent so much time with her mother and father making prints of Ikki’s work, she’s no stranger to the process. Today, Amy has her own line of custom prints, tumblers, T-shirts and shoes, which she sells through her online shop It’s A Little Over The Top. “I never did go to art school,” Amy says. “I think I was scared of competing with them.”

Ikki and Polly were known on the island for their vastly different, yet compatible, styles. While Ikki’s stark linework in his silkscreens and acrylic paintings earned him the nickname Picky Ikki from his best friend and printer Dennis Clark, they still represented his quick wit and sense of humor with playful scenes and names like Oh, Go Fly A Kite! and Oh, Fiddler Sticks! His wife’s mixed-medium work also played on island themes, mixing shells, tiny figurines and other found items with her own woven patterns. While his work may be famed, both of them were considered instrumental in shaping Sanibel’s arts scene and recognized for their contributions to the community. The couple donated art to various charities on the island, and Ikki’s designs were a staple on T-shirts and fliers for the Rotary Club of Sanibel-Captiva’s events, plus other local organizations. Saari points out, as we look at some of Ikki’s work in Tower Gallery, even his library card has one of the artist’s creations on it.

Since the couple used profits from works to pay the bills, the Matsumotos rarely saved copies of Ikki’s works. Between Amy, Saari and Polly, it took about three years of searching social media, calling galleries and talking to local collectors to complete the book, which includes more than 100 of his creations, along with work done by Polly, who passed away in 2019 before the book was completed. The Alliance for the Arts’ retrospective for the couple last February drew a passionate crowd for both artists. “I had never experienced such strong emotions, like the people that loved your mom’s work,” Saari says to Amy with the waves crashing in the background as we make our way to our last stop, the umbrella-lined Bowman’s Beach. “I mean, there were tears in their eyes. And then everybody knew Ikki, and we knew he was already kind of a legend here. But, your mom’s fans surprised me.” Amy responds proudly, “They loved her, too.”

We end our tour where it all began: out on the beach, waiting for the sandpipers to flock to the waves as Ikki did, looking at the shells scattered throughout the sand that may have made a necklace for a teenaged Amy or provide the finishing touch woven into one of Polly’s 3-D creations. And I know, this was, and always will be, the Matsumotos’ island.